You probably know this case well, but I’ll recap it anyway. Malwarebytes makes anti-threat software. Enigma makes competitive offerings. Malwarebytes classified Enigma’s SpyHunter4 and RegHunter2 programs as malicious, a threat, and a potentially unwanted program (PUP).

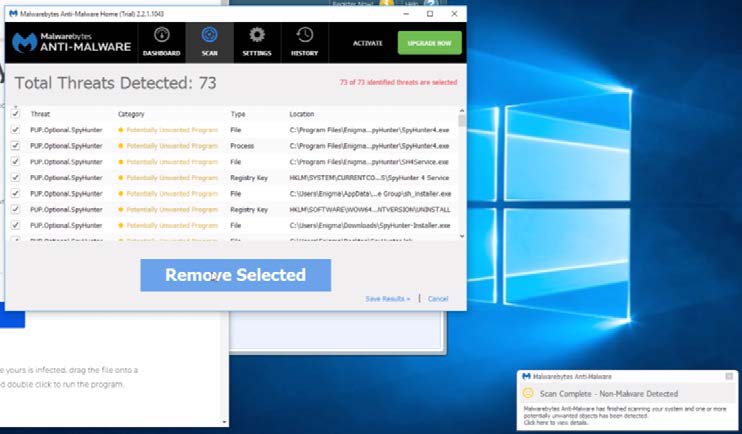

This screenshot shows Malwarebytes’ interface. The green “upgrade now” button plays a key role in the court’s latest analysis:

Enigma sued Malwarebytes for its classifications in 2016, back when Obama was still president. This case should have been easily resolved by Section 230(c)(2)(B) per Zango v. Kaspersky. Instead, it has horked Internet Law in three major ways:

- The Ninth Circuit created a new Section 230 common law exception for “anti-competitive animus”–some undefined principle vaguely rooted in antitrust law. That allowed the case to survive the first motion to dismiss. The new exception has added no value to the jurisprudence. Instead, it casts a nebulous shadow over many Section 230 defenses.

- The Supreme Court denied Malwarebyte’s appeal. Nevertheless, Justice Thomas issued a “statement” in connection with that denial, which he self-admittedly wrote “without the benefit of briefing.” The statement mused about the ways Section 230 jurisprudence has gone wrong. Justice Thomas’ statement is terrible, both procedurally and substantively. Despite that, Federalist Society judges treat the statement as more persuasive than, you know, actual precedent.

- After remand, the case went back to the Ninth Circuit, which held that anti-threat classifications might be Lanham Act false advertising. Say what?

Today I’m blogging the district court decision after that remand. The result is ugly. The court horks the law for a fourth time, reinforcing how this case is a wrecking ball to Internet Law. I really do hate this case.

Lanham Act

Commercial Advertising or Promotion. The Lanham Act only applies to “commercial advertising or promotion.” This case reaches that question in an awkward fashion.

Malwarebytes offered try-before-y0u-buy software, which increases consumer demand by identifying a larger number of threats; that scares consumers into upgrading the free trial. (This need to get consumers to “act now” is one of the reasons why the D2C anti-threat software industry is dubious). In theory, Malwarebytes will boost conversions even more if it rates its competitors as threats, reducing their interest in the alternatives. Thus, if you squint, you might see how Malwarebyte’s classification of Enigma contributes to consumers’ buying decisions.

This reasoning creates some problems, though. First, the same logic would extent to all of the threats identified in the try-before-you-buy experience, not just the threat designations of direct competitors (though non-competitors may not have Lanham Act standing). That putatively means that the court would characterize all threat identifications as “advertising.” Second, the classifications work in both the try-before-you-buy and the purchased software, so the classifications either are false advertising after the sale has been made (which makes no sense–the deal is done) or the exact same classifications have different legal statuses pre- and post-purchase. If it’s the latter, then treating editorial content offered on a try-before-you-buy basis as advertising seemingly allows false advertising plaintiffs to sue over what is clearly editorial content (which is what I think happens in this case).

Having been reversed twice by the Ninth Circuit in this case, the judge cautiously the inferences in favor of Enigma this time. Thus, we get statements like “there is no categorical rule that in-product statements are immune from Lanham Act claims.” That’s true, because common sense usually forecloses that question.

The court says Enigma’s allegations that “the challenged designations were made in a marketing context for a potential transaction” make this a “close question,” so the court uses the Bolger test for determining commercial speech.

Bolger Factor 1: Advertising

the first Bolger factor—whether the statements are an advertisement—to fall slightly in favor of the conclusion that the challenged designations are commercial speech. Although the words at issue—“malicious” and “threat”—are not themselves advertisements, Enigma has alleged facts permitting an inference in its favor that Malwarebytes makes the speech in an advertising context. For example, Enigma alleges that the designations appear during a free trial period designed to showcase Malwarebytes’s product capabilities, so that the users experience “a marketing mechanism for Malwarebytes to entice users to ultimately purchase the Malwarebytes products.” Enigma also alleges that Malwarebytes displays the challenged speech directly alongside buttons with phrases such as “Upgrade Now.” Given these allegations, the Court finds that Malwarebytes’s labeling of Enigma’s competing anti-malware software as a “threat” or “malicious,” especially when combined with the button linking the user to a payment space, is an advertisement for purportedly superior MBAM products

In support of the last sentence, the court cites Enigma v. Bleeping Computer, where the court found that self-laudatory blog posts were ads. But this case involves the actual product itself, not promotional blog posts published independently of the product.

More generally: most commercially vended editorial items uses teasers/tasters as part of its marketing/advertising. Does this ruling indicate that doing so converts all of the editorial content into an ad for…the content itself? Consider an analogy: book publishers routinely give away free promotional copies of books to reviewers and others. If a book trashes a rival publisher and that part is included in a book excerpt used as marketing for the book, what result?

Bolger Factors 2 and 3: Reference to Specific Product and Economic Motivation.

Enigma alleges that Malwarebytes applied the challenged designations to Enigma’s SpyHunter 4 and RegHunter products within Malwarebytes’s own MBAM products, including AdwCleaner. Enigma also alleges that Malwarebytes has an economic motive to designate Enigma’s competing anti-malware products as “threats” and “malicious,” namely, to persuade users to buy MBAM products rather than Enigma’s competing anti-malware products, and thereby increase Malwarebytes’s sales, profits, and market position.

These allegations are good enough to reach the counterintuitive conclusion that an anti-threat software vendor’s threat classification is a “commercial advertisement or promotion.” Mind-blowing.

Disseminated to the Public.

the SAC’s allegations permit an inference that Malwarebytes disseminated the challenged designations to the relevant purchasing public. First, Enigma alleges that Malwarebytes’s free version includes features such as protection from malicious websites for 14 days—after which the only function of the free version is to clean up an already-infected computer—and that Malwarebytes uses its free trial directly as a marketing mechanism for its paid MBAM products. Second, Enigma alleges that users who had already downloaded and installed its products and subsequently ran an MBAM scan would find Enigma’s products quarantined and labeled a “threat,” and that Malwarebytes users who sought to download and install Enigma products would also see the “threat” label and quarantine action.

Falsity

[Enigma] has sufficiently alleged that the designations of “threat” and “malicious” were materially deceptive to a substantial segment of the relevant purchasing population. Enigma alleges that it received hundreds of complaints from users of its products who had viewed Malwarebytes’s designations, and that the complaints included statements indicating that the users understood the designations to identify Enigma’s products as malware.

The New York false advertising and tortious interference claims also survive the motion to dismiss.

Implications

Kudos, I guess, to Enigma’s lawyers. Having lost twice in the district court, they turned it around on the third try. In particular, they more compellingly won the battle over the narratives. Storytelling FTW.

I assume this case is headed back to the Ninth Circuit for the third time. How much money do these litigants have to fight a court battle over nearly a decade?

However much money they had, this case is a cautionary tale about the legal risks of anti-threat classifications. I imagine that most anti-threat software vendor will never again classify another anti-threat software vendor as malicious, a threat, or a PUP, even if those classifications are entirely appropriate and in consumers’ best interests. This is how the courts–especially the Ninth Circuit–have been indirectly undermining cybersecurity.

Case Citation: Enigma Software Group USA, LLC v. Malwarebytes, Inc., 2024 WL 2883671 (N.D. Cal. June 6, 2024). Prof. Tushnet’s coverage.

Enigma v. Malwarebytes Case Library